Life, Liberty, and Lifelong Learning

What can the Founding Fathers teach us about happiness, and learning, in the age of AI?

On the afternoon of April 30, 2022, more than 157 years after the Civil War, I found myself walking Pickett’s Charge on the hallowed grounds of Gettysburg National Military Park in south-central Pennsylvania. It was an unseasonably-warm day and, in the sun at least, felt like an early-July march.

I wasn’t walking alone, nor was I with family or old friends; I was traversing the path of Pickett’s division with fellow working professionals of all ages from around the country: non-profit leaders, lawyers, physicians, consultants and young graduates still finding their way. And I myself was the CEO of an international investment firm I’d launched years earlier drawing on a decade of executive experience at Google and Twitter in the U.S. and across Asia Pacific.

Our fearless leader and teacher that day - indeed for a few days that week - was renowned Civil War historian James McPherson, the author of the Pulitzer-prize winning Battle Cry of Freedom.

Sure, most of us were alumni of Princeton University, where Professor McPherson has long taught and I’d previously served as a Trustee. And, yes, we were participating in “Princeton Journeys,” a program designed to strengthen bonds between alumni and their alma mater.

But, still, while I finished an e-mail and watched a perspiring, out-of-breath Fortune 500 executive lead a Zoom call as we traced the topography towards Cemetery Ridge - and Professor McPherson reflected with great poignancy on the test and toll of that early July day in 1863 - I couldn’t help but wonder:

“Why are we all here, and what, exactly, are we pursuing?”

Nearly three months earlier, in the early hours of February 3, I left my home in Charlottesville, where I’d lived for four years, and drove south through the Shenandoah Valley and up the Blue Ridge Mountains towards Blacksburg, the home of Virginia Tech.

On my mind as I drove through a freezing-rain-fueled “wintercane” of sorts was, mostly, a yearning to learn, and grow.

In recent years, and undoubtedly accelerated by the Covid pandemic, I’d begun seeking out a steady stream of education and experiences - online and offline - to scratch a learning itch I didn’t quite know how to explain. Friends and acquaintances around the country seemed to be traveling in similar learning lanes, too. Maybe it was behavior confined to my bubble or, maybe, we were among millions nationwide who, according to Pew Research, had by the pandemic begun racing towards platforms like Coursera, Khan Academy, Stack Overflow, YouTube and others as learners.

What kind of ailment were we treating while trading texts about PBS features on spacetime, MIT OpenCourseWare lectures on machine learning and podcasts centered on the afterlife of Ancient Greece? Why did growing numbers of friends from across a range of pursuits seem to seek refuge - and nourishment - in short-burst learning excursions convened by the Chautauqua Institution and the Aspen Institute? If “biohacking” rose to the fore during the health-and-well-being scares of Covid, what were we hacking: digital literacy? Or a kind of human literacy? It felt like a self-medication of sorts and, frankly, I wasn’t sure it was meeting the mark.

Having dropped out of business school more than a decade earlier, I often wondered, “Should I finally get that Master’s or Executive MBA? Maybe a law degree? A Ph.D., even?” Needless to say, my kids grew wary of my off-and-on back-to-school ruminations.

So, when Dr. Sylvester Johnson, one of the nation’s leading scholars of African American religion and, then, the director of Virginia Tech’s Center for Humanities, asked if I’d like to spend a few hours on campus learning about the university’s growing commitment to the humanities, I thought, “Why not?” After all, he and I had served since 2019 as board directors of Virginia Humanities, one of the nation’s 56 humanities councils and I, a college history major who’d built a career as an entrepreneur and executive in technology, had grown to believe the humanities needed to evolve a refreshed posture in our inescapably digitally-dressed world.

I’d never been to Blacksburg before. I’d loosely heard of it through former Google Chairman and CEO Eric Schmidt, a mentor who had two decades earlier recruited me to serve as his speechwriter. Eric grew up in the small mountain college town on the Eastern Continental Divide in the ’60s and ’70s. “A chance to connect the dots,” I thought.

I arrived late - and wet - for breakfast with Dr. Johnson. “What did I miss?” I asked, smiling, recalling the song from Hamilton featuring Thomas Jefferson.

But by the time I left Virginia Tech, inspired by the institution’s motto - “Ut Prosim” (That I May Serve) - I was asking a different question on the ride home as the rain subsided and the skies cleared: “What if I took a career detour to build the humanities-centered, science-curious lifelong learning experience I’d long been in search of?”

Earlier this year, nearly three years to the day after walking Pickett’s Charge, I found myself walking a different military site, with a different historian and a different group of lifelong learners: at Arlington National Cemetery with Dr. Paul Quigley, director of the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies.

On our walking tour was the graduating Class of 2025 of the Virginia Tech Institute for Leadership in Technology, which I’d founded two years earlier to offer the nation’s first mid-career degree in the humanities to learners and leaders from across fields and functions, a first-of-its-kind lifelong liberal arts credential with an eye on both the timeless sensibilities of the arts and the timely skills of our AI age.

We were in Washington to celebrate the graduation of this group of students from our one-year program, one which by then had drawn fellows from five countries, ten states and two-dozen companies and causes ranging from cybersecurity to conservation.

Together, each year, they had studied history and philosophy, engaged with literature and creative writing and immersed in place and faith - with an eye, too, on the origins of artificial intelligence, and its opportunities.

Students had read and written about scientists Bohm, Einstein and AI pioneer Fei Fei Lee, but also texts from 9th-century China, tales from Elizabethan England and a letter from a Birmingham jail. Their guest speakers had ranged from National Geographic Board Chair Jean Case and former Howard University President Ben Vinson to venture capitalist Katie Stanton and “Father of the Internet” Vint Cerf.

And along the way, I myself had spent a year working with OpenAI, helping guide the company’s entry into India and emerging markets, and served as Chairman of the National Humanities Center.

“A dream realized,” I thought, as I took in afternoon views of our nation’s capital, and of President John F. Kennedy’s grave, from Robert E. Lee’s Arlington House. “How did we get here?”

While this story culminates in Southwest Virginia, from where we ultimately envisioned, entrepreneur-ed and evangelized a more capacious, current and connected vision for the humanities and lifelong learning, the story begins, I think, in Philadelphia and an unseen but self-evident truth expressed at our nation’s founding in 1776.

In that summer 249 years ago, the Founding Fathers invoked bedrocks of American self-governance in the Declaration of Independence, and included “the pursuit of happiness” as an inalienable natural right, alongside life and liberty. But what exactly did they mean by “happiness”?

Were they referring to matters of the hearth, namely property and economic fulfillment? To matters of the heart, including the cultivation of a kind of inner peace and tranquility? Or did they, with an eye on an ever-evolving nation, have their gaze elsewhere?

As I was rekindling my commitment to the humanities, I wasn’t the first to wonder.

Indeed, scholars have been weighing in on this question for years, as have storytellers. One - the filmmaker Ken Burns - has been particularly articulate and affecting for me as I grew to understand that recasting the humanities to realize a new, future-proof dynamism in our culture might constitute an act of reclaiming our revolutionary roots, too. Burns, whose latest film The American Revolution premiered last month, recently appeared on CBS’s Face the Nation and was unequivocal in his sense of what happiness “pursuit” the founders had in mind:

“Lifelong learning,” he said.

“The pursuit of happiness is not the acquisition of things in a marketplace of objects, but lifelong learning in a marketplace of ideas,” Burns continued. “To continually educate yourself is what was required to sustain this republic and I think that’s what we’ve gotten away from.”

Jefferson, the Declaration’s lead author and a student of the Enlightenment, long situated happiness with learning, and was known to keep and recommend extensive reading lists for self-improvement. He wrote in his later years: “I look to the diffusion of light and education as the resource most to be relied on for… advancing the happiness of man.”

Burns is not the only contemporary I came across who emphasized, emphatically, the Founders’ belief in lifelong learning, and personal transformation, as essential, and even existential, to the American experiment.

Scholar Jeffrey Rosen, the author of The Pursuit of Happiness, has also highlighted the Founding Fathers’ emphasis on personal self-mastery as a necessary path to personal and political happiness. “...Happiness requires a life devoted to the pursuit of self-improvement so that we can be our best selves and serve others,” Rosen remarked at an event convened last year by the National Constitution Center, where he serves as President and CEO.

“So moved,” I’ve said to myself over the years as I’ve heard voices reflecting on what Walter Isaacson calls “the greatest sentence ever written,” the topic, and title, of his book published on November 18.

“But how might we gauge where we are as a nation today?,” I’ve wondered, too, including on that early 2022 drive to Blacksburg. “And if, as Burns argues, we’ve ‘gotten away’ from this spirit, what might we do to move forward a nation-scale, always-on culture and capacity of lifelong learning on the eve of 250 years of American independence?”

My family and I did move to Blacksburg, and the old, elder mountains of Appalachia, in the summer of 2022, and I joined the faculty of Virginia Tech as a Professor of Practice and Distinguished Humanities Fellow.

Struck immediately by the big, mountain-rimmed skies of our town, and the blue-sky, bottoms-up spirit of experimentation and entrepreneurship that permeates the university, the atmosphere seemed ripe for wrestling with big questions, and big answers. What seemed to be in the air then were questions, accelerated by Covid, about how the humanities might recover from enrollment declines and how higher education might rediscover its pre-pandemic value proposition. What we didn’t yet know was we were on the precipice of a zeitgeist set to be consumed by large language models - and equally large questions about learning, living and leading.

“What singular contribution could I make from within higher education,” I thought, “with an eye on the natural right of lifelong learning as a North Star?”

My initial, cursory glance at institutions in the business of higher knowledge presented, it would seem, a cloudy picture. After all, confidence in higher education has fallen drastically in the last decade, enrollments in the humanities are declining, Ph.D. pipelines are thinning, and baseline interest in graduate programs may be softening, too.

But, the entrepreneur in me wondered, notwithstanding this murky picture of higher education, what might a portrait of higher learning reveal? Bluer sky, I found.

Nearly three quarters of U.S. adults call themselves lifelong learners, more than half of Americans on YouTube report having used it to learn how to do new things, nearly nine in ten podcast-listening Americans say they do so to advance their learning, and 60% of adults say they use AI for “self-directed learning.” What should we make of all this?

Yes, we live in an era of deep, disheartening division and distance, I thought, but we also live in an era in which Americans seek and strive to learn on their own and from one another - synchronously and asynchronously - in transformational ways. The depth and breadth of wisdom available in the marketplace of ideas - and wisdom being tapped, citizen-to-citizen, prompt-by-prompt - is awe-inspiring and worth building from, not breezing past.

Sure, some among us may be quick to regard much of this activity as unsophisticated noise. But, I wondered, what if we actively choose - as my former Knight Foundation colleague Trabian Shorters reminds us when championing asset-framing as a singular cognitive skill - to detect positive signal in this noise? This attitude of seeing the learner and leader in fellow citizens can be profoundly shape shifting: it’s what, fifteen years ago, on the heels of the Great Recession, inspired me to co-found Michigan Corps and Kiva Detroit, online civic-engagement platforms cultivating the citizen - indeed, the learner and leader - in everyone committed to these places. “Ask what you can do for your state,” we proclaimed.

After my leap-of-faith move to Blacksburg, here’s a question I began to ask in higher education circles: in an AI-leading nation in which credentials themselves are being called into question, what should we make of the fact that microcredentials - more than 1 million and counting in the marketplace - are booming?

It would be easy to rest on these little laurels.

Headwinds abound in higher education, yes, but the marketplace is responding to fill the gaps, isn’t it? After all, big technology companies like Amazon, Google, Microsoft and OpenAI have committed themselves - including at an event convened by the White House in early September - to a new wave of must-have technology training. If the 2010s were marked by efforts to evangelize coding, albeit with mixed success, this decade should, it would seem, center on expanding AI literacy. Right?

Elsewhere, in both the public and private sectors, efforts to reimagine and refresh learning at all levels abound, too, including at the National Humanities Center and Transcend Education, whose boards I serve on. Thousands of flowers are undoubtedly blooming.

And at our universities, some might suggest business, education and public policy schools have long been adequately filling lifelong learning gaps. After all, for the better part of a century they have inhabited the language of leadership education, offered bespoke upskilling experiences for professionals and developed revenue-generating practices centered on helping companies evolve their respective workforces. Many have grown an appreciation for the value of soft skills, too.

And outside of professional schools, universities - via continuing education divisions - support a wide range of customers seeking more immediate growth and know-how, as well.

So why offer a fix to what doesn’t seem broken?

Because here’s another self-evident truth, one which Burns gestured at: considering the trend lines around how young people view school and college, the state of our civic discourse, and growing economic pessimism, it’s also plainly clear a nation-scale, institutionally-reflected, politically-prioritized spirit of lifelong learning has not taken hold.

Perhaps in offering a multitude of training experiences for organizations centered on immediate learning outcomes, higher education has overlooked the cultivation of a lifelong learning movement among individuals centered on the intrinsic value of learning itself.

I didn’t know precisely what to do, but I did know that the humanities needed to enter the chat.

“The acronym ‘STEAM’ doesn’t seem to do justice to the role of the liberal arts, does it?” I asked Scott Hartley, the author of The Fuzzy and The Techie, while standing on stage at Virginia Tech’s Haymarket Theater on a cold winter morning in February 2023 alongside university president Dr. Timothy J. Sands.

I was making reference to a once-pervasive acronym that places the “arts” at the center of the ever-more-pervasive “STEM” fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

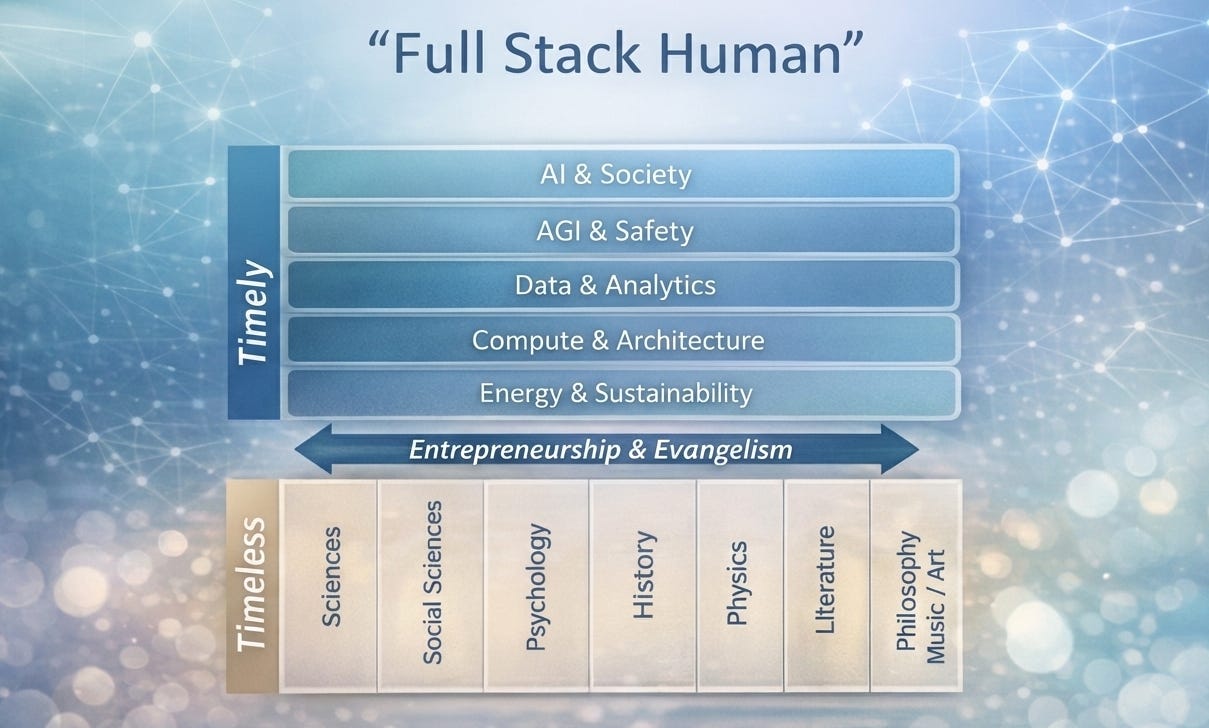

“No, you’re right” Hartley replied. “We need something more coherent – and compelling.” He paused for a moment and then asked the two of us: “How about ‘full stack’ human?”

“That’s it!” I said, before rushing to introduce Hartley and Dr. Sands to the audience gathered for their fireside chat to conclude our second annual Humanities Week. I knew immediately this frame - “Full Stack Human” - had the substantive and storytelling value the landscape, and even my inner discourse, needed. It might even strike a chord with both humanists and technologists given their shared affinity for “stacks” of one sort or another.

As I took my seat, I wondered, “What does the ‘Full Stack Human’ of the future look like, and what might it mean to see human flourishing through the prism of a full stack?”

Together with Hartley, I imagined a three-layer stack: (1) undergirded, as infrastructure, by the timeless introspection, intuition, and imagination the arts and sciences trigger; (2) built upon with an appreciation for the kind of entrepreneurship - and evangelism - it takes to break through with one’s calling; and (3) topped off by timely fluency in today’s technology trends, whatever they may be.

If the gravitational pull of our culture, today, pushes us towards the top of the stack, a layer that is constantly in flux, could we - inspired by our Founding Fathers, and the quiet experiences of many lifelong learners - recast the humanities as inhabiting its foundational layer?

By the spring of 2023, a year after walking Pickett’s charge in Gettysburg, I resolved with conviction, “If I build it, they will come.”

With the support of Virginia Tech, I launched our Institute for Leadership in Technology that summer, offering the nation’s first leadership degree grounded in the humanities - and first-of-its-kind lifelong liberal arts credential - to rising leaders coming of age in this time of generative artificial intelligence. Immediately, many hundreds from around the world reached out to say, “Yes, finally!”

Since then, each year our group of learners from a range of communities, companies and causes engage together on questions of what it means to be human, and reflect on what it means to be a learner and leader across the “full stack.” They do this not to serve immediate ends, but to serve higher learning itself, and the other-centric - and, our Founding Fathers might argue, happiness-inducing - muscles of higher leadership that the pursuit of knowledge for knowledge’s sake cultivates. It turns out curiously immersing oneself in learning the timeless because it has essential value can buttress one’s life - and leadership and learning practice - in a culture already saturated with pressures to lean into on-demand timely technical learning.

Now in our third year, we have hosted leaders from companies in Silicon Valley and the Shenandoah Valley, entrepreneurs championing causes ranging from oral history to public-interest technology and public servants with experiences in aerospace engineering and national defense.

At a time when institutions nationwide are confronting interrogating headwinds, our Institute is as of this year not alone in suggesting that new tailwinds - and new constituencies - might be generated by embracing the creation of lifelong-learning bridges for more of our fellow citizens, bridges whose mission is the cultivation of a commitment to learning for learning’s sake.

This past summer, both the State University of New York at Potsdam and Northeastern University President Joseph Aoun began to advance lifelong learning paradigms, too, inclusive of the humanities.

I’ve wondered often, particularly this year, “What if navigating these heady times for institutions of higher learning included, first and primarily, seeing and serving a nation of unseen and unmet learners? What if the vitality of higher education’s knowledge-seeking mission rests on the vigor it brings to its knowledge-imparting mandate? And what if lifelong learning evolved from a module that is incidental and improvised - housed in this or that school - to a mission that is integral, intentional and inspired, with newfound appreciation for the centrality of the humanities?”

Yes, I’ve grown to believe, universities must continue to offer one-way bridges that meet learners of all ages with programs that enthrall and educate instrumentally: with tools of the trade; entrepreneurship know-how; and AI mastery. But we also need two-way bridges that meet learners where they are not just with an eye on retraining and refreshing employability, per se - but with a more complete, inspired posture that, first, sees and salutes an existing learned spirit, and situates and storytells it as a civic virtue. And then, critically, offers education and experiences that emphasize learning-for-learning’s-sake as the quintessentially-American leap of faith.

Here, the institutional humanities can lead with urgency as the foundational layer of what it means to be a “full stack” human, reminding us of their particular power to nourish the soul, humble the mind and stretch the length, and depth, of human purpose.

Beginning 2023, while pitching my Institute to anyone that would listen, many would ask: what precisely are the humanities? Which departments are in? Who’s out? I crafted a six-word poem to capture a new, capacious essence:

Awe and wonder

In the other

In our culture of immediacy and the instrumental, education and experiences that cultivate a lifelong spirit of awe and wonder in human, and non-human, others - past, present and future - may not just be the antidote to what ails us, but the universal aspiration our Founders intended.

What could be more apropos ahead of 2026 and America’s semiquincentennial?

Many universities ask me to reflect with them directly on opportunities to refresh their approach to humanities education and evangelism. I often begin by asking, “What might a university founded today, one which takes seriously both advanced research and accessibility to learners across the full stack, look like?”

On the heels of Burns’ documentary and on the eve of America’s 250th, a more inspired starting point for institutions of higher learning, and indeed all public institutions, might be to first reflect with more depth on the hidden, happy pursuit in our nation’s founding document:

First, by seeing in our Declaration of Independence an emphatic declaration of our inalienable natural right to a vibrant - and lifelong - flourishing of the mind. What if this was a sacred American ideal, and one which sat at the center of our national sightline? Indeed, sitting with this truth before stirring to action is essential. Considering the way our Declaration’s writers situated happiness with learning and it with civic virtues, imagine our Constitution - whose 227th anniversary we celebrated this past Constitution Day - opened with: “We the Learners”?

Second, by speaking of and storytelling the learners among us as pursuing among the most noble, and quintessentially American, of civic duties. When we see and celebrate the lifelong learners among us on stages big and small, we have the beginnings of culture change. I’ve found language matters, too: well-intentioned headings like “professional development” and “upskilling” can downplay the profundity of what self-improvement constitutes. Our civic culture, and universities, can no longer afford to leave the rise of this permission structure, one which assertively lifts up lifelong learners to the top of our city on a hill, to chance.

And finally, by shaping concrete bridges of opportunity into lifelong learning for all Americans, no matter their season or station in life. This would entail reflecting on how learning happens in an AI-ascendant era, what is to be learned and what initiatives need our recommitment – and which need reimagining. Such bridge building will rightly compel institutions to rise and wrestle with hard questions. Here’s one: what is American excellence, and the quintessential American metric? Only the view presented by majors and minors, Ph.D.s and placements? Or the broader vista featuring learners, askers, seekers, searchers and pursuers, too?

The first step in realizing a nation of 350 million learners, then, may be to first see a nation that is striving to learn. Imagine every major American institution resolving as its mission to meet the full-stack learning needs of new constituencies of learners, undergirded by the humanities? Or the body corporate mainstreaming learning leaves and credits for employees? What if, in addition to AI literacy, governments, corporations, foundations and universities dwelled on a more foundational measure of an active lifelong learning literacy?

After all, to commit to a life of full-stack learning, and to be seen as such, not only echoes the learning logic that powers AI - its pretraining phase, that is - but is also the most durable way to assure one’s ability to keep up with technology trend lines, no matter when they emerge and where they extend.

In late 2022, weeks after settling in Blacksburg, I found myself at the River North Correctional Center, a Level IV prison in far Southwestern Virginia, near the North Carolina border, in a town called Independence. There, alongside Dr. Johnson, I observed a seminar he led centered on Zora Neale Hurston’s 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. I watched a group of inmates - many incarcerated for decades for violent crimes - wrestle with questions of self-discovery and independence, love and relationship, race and gender, nature and fate.

Looking back at my notepad from that day, one scribble stands out:

“Somehow, I’m envious…”

Removed from our what-have-you-done-for-me-lately, hall-of-mirrors culture, these fellow human beings were - before my eyes - awakening an innate spirit of learning for learning’s sake, and I could see the light, and windows, it offered them, even in their circumstance of resignation. It was a kind of alchemy.

“What if our culture ‘out there’ featured people young and old grounded not merely in today’s know-how, but a spirit of how and knowing for all time?” I wondered.

As I learned there and in my subsequent work at Virginia Tech, deep down, learners in our AI-ascendant era crave belonging, being seen and braving new worlds of knowledge just as much as - and maybe even more than - credentials and their immediate marketability.

Burns is indeed right and our Founding Fathers were prescient: in our AI-enables-everything landscape, in which opportunities to activate one’s sense of purpose have never been more proximate, and the need to keep up with what’s new feels more pressing than ever, committing to a lifelong pursuit of learning for learning’s sake, of things changing and unchanging, and to seeing the learner in all Americans, may be the highest “responsibility of citizenship” - and the happiest pursuit of all.

Excellent essay, well written and appropriate for these times.

I really enjoyed reading the origin story! Great piece, Rishi!